Home visiting during pregnancy and child’s first years of life is an important preventive and health promotion strategy for supporting early child development, the wellbeing of family/caregivers and responsive parenting. It is unique because it happens in the domestic context, and often home visitors are the first professionals to meet the most vulnerable families, who usually do not come into contact with health facilities. It is crucial for home visiting services to utilize the qualified, well-trained, and supported home visiting workforce’s potential.

The need to ensure and maintain the quality of home visiting programs, requires regular monitoring and analysis. The Home Visiting Workforce Needs Assessment Tool (HVWNAT)i and its accompanying User’s Guide were developed under the Early Childhood Workforce Initiative (ECWI)ii to support Ministries, government agencies, and other relevant stakeholders to review, analyse and reflect on the status of home visiting programs, to identify workforce strengths and gaps, as well as to prioritize areas for government attention and actions at either the sub-national or national levels.

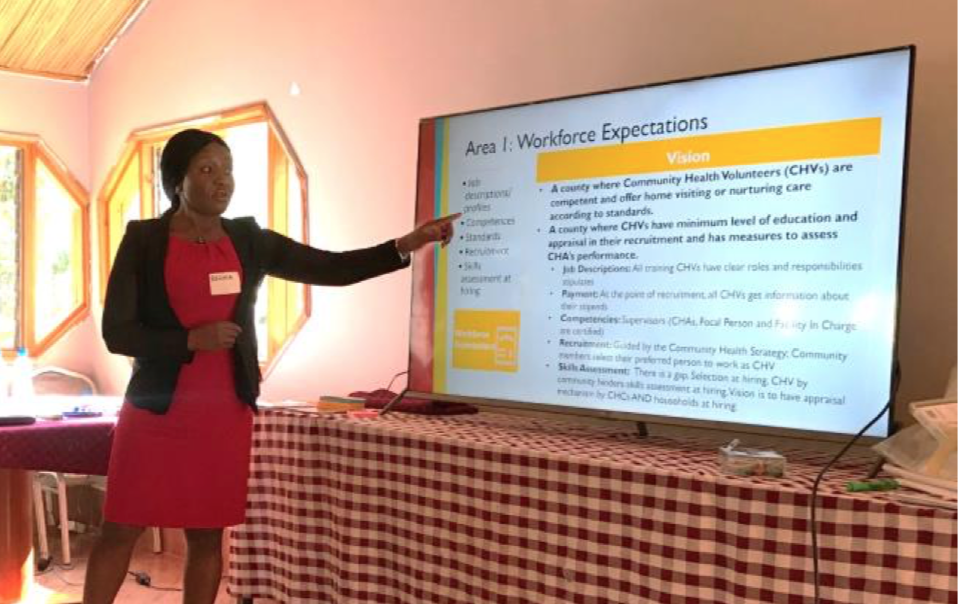

The Tool focuses on home visitors who work directly with young children and their families, as well as supervisors and trainers. It covers seven areas relevant for the quality of the work of home visitors: four areas address conditions that impact home visitors’ work on a day to day basis (Area 1: Workforce Expectations, Area 2: Curricula, Materials, and Resources, Area 3: Training, Supervision, and Career Development and Area 4: Workforce Conditions) and three areas that impact home visitors’ work at system-level (Area 5: Program Design, Area 6: Enabling Environment and Area 7: Monitoring and Quality Assurance). The Tool was designed to be inclusive and facilitate knowledge exchange and dialogue among a diverse range of stakeholders across roles, sectors, and levels of government. Thus, each Area of the Tool is organized around a series of goals and measures which are followed by questions for reflection.

The Tool focuses on home visitors who work directly with young children and their families, as well as supervisors and trainers. It covers seven areas relevant for the quality of the work of home visitors: four areas address conditions that impact home visitors’ work on a day to day basis (Area 1: Workforce Expectations, Area 2: Curricula, Materials, and Resources, Area 3: Training, Supervision, and Career Development and Area 4: Workforce Conditions) and three areas that impact home visitors’ work at system-level (Area 5: Program Design, Area 6: Enabling Environment and Area 7: Monitoring and Quality Assurance). The Tool was designed to be inclusive and facilitate knowledge exchange and dialogue among a diverse range of stakeholders across roles, sectors, and levels of government. Thus, each Area of the Tool is organized around a series of goals and measures which are followed by questions for reflection.

The home visiting system in Serbiaiii

Serbia is well known for its well developed and organized home visiting system under the Ministry of Health, and for the openness to continuous learning, evaluation of the status of the service and innovative approaches in supporting continuous professional development of the visiting nurses (polyvalent patronage nurses).

Patronage nurses operate on the Municipality level and are part of team of the Public Health Centers. Their main role is to help families to recognize their own capacities and identify solutions for the challenges they face. Through regular home visits, the nurses build partnerships with families based on mutual respect and confidence, and work together with parents/caregivers to provide every child with the best start in lifeiv.

In recent years, under the Playful Parenting programme, UNICEF, with the support of the LEGO Foundation, the Government of the Republic of Serbia and partnersv, have put a lot of effort to develop models to foster supportive parenting and introduce the innovative polyvalent patronage services. The new training packages promoting nurturing care were developed and accredited, which were used to train more than 400 visiting nursesvi. So far the innovative services have reached more than 20,000 parents–30 percent of which are fathers–in 34 cities and municipalities across Serbia.

Support country efforts: technical assistance in Serbia

In 2023, with support from Bernard van Leer Foundation (BvLF), Zorica Trikic, Senior Program Manager at the International Step by Step Association (ISSA) and the coordinator of the ECWI, provided technical assistance (TA) to partners in Serbia, including UNICEF Country Office and their partners - the Ministry of Health, the Institute of Public Health of Serbia “Dr Milan Jovanovic Batut”, and the City of Belgrade Institute of Public Health. The TA was tailored to the needs of the national partners, and the HVWNAT was used as a primary tool in the process. The TA focused on:

- Building a body of 15 national facilitators/trainers (Training of Trainers - ToT) to empower independent usage of the Tool;

- Facilitating the dialogue on Monitoring and Quality Assurance with 26 participants from all over Serbia, in cooperation with Institute of Public Health of Serbia “Dr Milan Jovanovic Batut” based on Area 7 of the Tool;

- Contributing to the development of the supervision system in Serbia by delivering training to supervisors and mentors, and developing a set of materials including guides and a competency framework for supervisors.

What did we learn about the potential of the Tool from our work in Serbia?

A successful learning is always a two-way street. We shared our knowledge with partners in Serbia, but we also learned a lot. We are grateful to all the partners and participants in the ToT and the workshop on Monitoring and Quality Assurance for their feedback, suggestions, critical questions, and opportunity to evaluate the Tool and gain better understanding of its value and usefulness.

Making visible the invisible

- The connection between, and the interdependence of, different areas presented in the Tool stress the need for a comprehensive approach to home visiting planning and for a more in-depth understanding of the complexity of the home visiting system and of the support that visiting nurses need for delivering quality services to children and families. Addressing only one Area of the Tool is not sufficient.

- Building self-esteem and a solution-oriented mindset in participants by raising awareness on what professionals can and must do to influence and improve the system that affects their performance and the quality of services they provide.

- Importance of discussion and professional exchange. While working with the Tool it became obvious how important it is to jointly define a vision for the home visiting service in general and for each area of the Tool, to find ways to build a common language and understanding between different professionals and connect all different professions relevant to the home visiting service around that vision; how important it is to overcome the "fragmentation" that exists within the health system, between sectors and communities.

- Inspiring participants to think about problems and topics that they had not thought about before.

The power of professional dialogue and elevating the voices of the frontline workers

- The Tool and the way it is used (e.g., participatory approach, building on strengths, small group work, work in pairs, exchange in the large group, aligning with others, overcoming differences through discussions) are valuable because it brings together a variety of actors, from frontline workers to national policymakers, for providing a forum and process to discuss the strengths and challenges of workforce-related policies, but also day-to-day challenges that visiting nurses face.

- The participatory and interactive way of working with the Tool elevates the voices of frontline workers, by providing the opportunity to voice and discuss their views, challenges, concerns, potential solutions with representatives of different institutions and levels of the health system.

- By using the Tool, communication between different actors is improved and shared understandings are built. This sets a fertile ground for future collaboration, and better vertical and horizontal cooperation within the health system, which is perceived by participants as fragmented, with insufficient data flow.

- Joint work and discussions inspire participants to critically review existing practices in order to improve them.

The Tool’s user friendliness

- The Tool can easily be adapted to the country context and needs. Reflection questions and even the measures suggested in the Tool can be aligned with national priorities, action plans and indicators for evaluation of the progress in the areas relevant for the country.

- The training for the Tool facilitators does not require significant time and financial resources if the trainers are experienced with interactive and reflective facilitation skills, and profound knowledge and understanding of the country home visiting system.

Multiple ways of using the Tool and its accompanying instruments

- Use the whole Tool and organize a 2-or 3-day workshop instead of using specific areas of the Tool separately, depending on the specific local needs, the level of accomplishment in different areas, and the time and resources available for organizing meetings and workshops. However, it is important to underscore that even when using only selected areas in the Tool, it is necessary to present the entire Tool, explain how all areas are interconnected and follow the participatory approach of the Tool.

- Reflection matrix, an instrument described in the User’s Guide (Section 3, pg. 39), is seen as extremely useful, informative, and applicable even independently from the Tool. Besides facilitating the process of assessing and reflecting on the level of implementation of specific measures (low, medium, high) and level of feasibility/level of difficulty to implement (low, medium, high) it creates an opportunity for intense small group discussions and valuable insights informing a shared understanding and planning.

From learning to action

- While using the Tool, participants learned a lot about the relevance of supervision and especially about monitoring and quality assurance, gained a better understanding of the needs, challenges and obstacles in the process of monitoring and quality assurance, as well as a better understanding of what patronage nurses need to be able to document their work and gain confidence that they are reaching all children and families with high quality services.

- During the small group work and discussion in the large group, participants learned a lot from their colleagues and their experiences, sharing good practices and solutions.

- While reflecting and discussing goals and measures defined in the Tool, participants came up with ideas for practical solutions and actions.

Key learnings informing the further use of the Tool

Besides learning about the Tool from a user’s perspective, the technical assistance delivered to partners in Serbia provided insights regarding requirements and recommendations in adapting the usage of the Tool to the context of the country, while maintaining its role to assess and plan to improve workforce performance and working conditions:

- Even when there is a high need to address specific components or aspects of the home visiting system – which are covered by one or more specific areas in the Tool – it is imperative to preserve the integrity of the Tool as a whole, the interconnectedness between the different Tool Areas, and the specific activities which support the implementation of the Tool.

- To demonstrate the accompanying instruments and the power of the participative processes in co-creating knowledge, ideas and solutions, it is highly recommended to use the Tool’s presentation to trigger interest and action in policy makers and other relevant stakeholders.

- It is highly recommended to adapt the questions for reflection in the Tool and align them with ones that are relevant for the partners/country context.

- To get the best result, it is crucial to stay open minded and focused on the needs of partners and Tool users, while guiding and accompanying them through the process of assessment, reflection, discussion, and planning guided by the Tool.

In addition to the takeaways closely related to the implementation process of the Tool, key insights from the entire technical assistance process surfaced and will highly inform the ECWI’s future work. When planning technical assistance to countries, a high degree of flexibility must be expected as their priorities and needs can easily change. Listening to and learning from country partners about local needs, constraints, and priorities will ensure the required readiness for adapting the process to the local context. The technical assistance provided to partners in Serbia was appreciated, alongside the flexibility and adaptability of the ECWI team supported by the BvLF.

i The Home Visiting Workforce Needs Assessment Tool was inspired by UNICEF’s Pre-Primary Diagnostic and Planning Tool.

ii The Early Childhood Workforce Initiative, led by the International Step by Step Association, the Arab Network for ECD, the Asia-Pacific Regional Network for Early Childhood, the Africa Early Childhood Network and Results for Development is a global, multi-sectoral initiative to bring more visibility to significance of the early childhood workforce (ECW) within the increasing narrative around the importance of early childhood development and of quality service provision for the youngest children and their caregivers, to lift up the voices of frontline practitioners, equip decisionmakers with the tools and resources needed to support the early childhood workforce at scale, provide evidence on best ways on how to recruit, train, retain, supervise and support the early childhood workforce and create opportunities for cross-country and cross-regional learning.

iii In Serbia the home visiting services are called polyvalent patronage services.

iv Serbia: Capitalizing on strengths - https://nurturing-care.org/resources/serbia/

v The project is being implemented by UNICEF and the Cabinet of the Minister for Demography and Population Policy in collaboration with the ministries of Health, Education, Social Welfare and Local-Self Government, with financial support from the LEGO Foundation.

vi https://www.unicef.org/serbia/en/press-releases/sixth-national-conference-early-development-and-parenting

Workforce Initiative (ECWI) co-convened a consultative workshop with the Government of Siaya County that was attended by Country and National officials, representatives from the County Department of Health and National Ministry of Health, representatives from civil society organizations, frontline workers, and others. The workshop was structured around the Home Visiting Workforce Needs Assessment Tool, which was designed to help government agencies and implementation partners reflect on the ways in which they can support personnel delivering home visiting across sectors for pregnant mothers and caregivers with children under 3, and has also been piloted in Bulgaria (see Box 1). In this interview, Denise Bonsu, a Senior Program Associate at R4D, chats with Dr. Elizabeth Omondi, County Coordinator for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child Health and Adolescent Health in the Department of Community Health Services in Siaya County, to learn more about her experience piloting the tool.

Workforce Initiative (ECWI) co-convened a consultative workshop with the Government of Siaya County that was attended by Country and National officials, representatives from the County Department of Health and National Ministry of Health, representatives from civil society organizations, frontline workers, and others. The workshop was structured around the Home Visiting Workforce Needs Assessment Tool, which was designed to help government agencies and implementation partners reflect on the ways in which they can support personnel delivering home visiting across sectors for pregnant mothers and caregivers with children under 3, and has also been piloted in Bulgaria (see Box 1). In this interview, Denise Bonsu, a Senior Program Associate at R4D, chats with Dr. Elizabeth Omondi, County Coordinator for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child Health and Adolescent Health in the Department of Community Health Services in Siaya County, to learn more about her experience piloting the tool.